Making Ethnobotany Exciting at Cedarburg Bog!

August 13, 2024 | Topics: Places, Stories

By Eddee Daniel—with a lot of help from Lee Olsen

The Merriam-Webster dictionary definition of ethnobotany is succinct to a fault: “The plant lore of indigenous cultures.”

Wikipedia fleshes the idea out a bit more: “Ethnobotany is the study of a region’s plants and their practical uses through the traditional knowledge of a local culture and people. An ethnobotanist thus strives to document the local customs involving the practical uses of local flora for many aspects of life, such as plants as medicines, foods, intoxicants and clothing.”

But I prefer the way Lee Olsen puts it:

“Ethnobotany is a vehicle for people to learn what native people know, and once knew, about the very land where we live. It is a way for us to relearn things about the plants that indigenous people understood and used—plants with which most of us have totally lost contact. There’s no end to the significance of the need to become familiar with all our plant neighbors, as well as the people whose land we took over. Ethnobotany is a multi-disciplined enterprise that combines linguistics, history, biochemistry, culture, mythology, geography, plant taxonomy, medicine, technology, survival, and food science.”

His passion for this subject has led Lee to teach a little bit of his vast store of knowledge and experience in workshops of varying lengths at the UWM Field Station in Saukville, which is adjacent to the Cedarburg Bog State Natural Area. Our three-hour session included a walk in the bog as well as classroom instruction and demonstrations. I for one wish I knew a lot more than I do about plants and the way they have been used (and are used) by native people. Let’s begin with the dramatic, shall we?

Some of this knowledge could save your life. Do you recognize this innocuous-looking white flower? Kinda sorta resembles Queen Anne’s lace. Parsnip is a closer match. But don’t touch! The Iroquois called it “suicide root” for good reason. Called water hemlock, it’s extremely poisonous. Related to the hemlock that Socrates is reputed to have died from—but far worse! The roots cause convulsions, vomiting, respiratory arrest, and death. There is no antidote. Properly used, however it is good for sprains and inflammation. It is quite common in the bog.

2,200-acre Cedarburg Bog State Natural Area is the largest, most intact and diverse wetland in Southern Wisconsin. It includes 245-acre Mud Lake, several smaller lakes and a small stream. Running water means, technically, that it isn’t actually a bog but a fen. While there are public access points at the north and south ends of the property, most of the bog is off limits to the general public except during special events—like this one! Then the gate is unlocked and we can enter the bog the only way possible without getting wet, on a skinny little boardwalk.

Common throughout the area, this isred osier dogwood (Cornus sericea), which often grows in dense thickets. There are five other types of dogwoods, all of which grow in the bog and surrounding woodlands. Lee is scraping off the outer bark to reach the inner bark, known by the Lakota and other tribes as kinnikinnick and used as a kind of tobacco or in a tobacco mixture for social, spiritual and/or medicinal purposes. (Three or four other unrelated plants in WI were also called kinnikinnick and used in the same way, except that their leaves are used instead of the bark.) The white gooey berries of the red osier dogwood can be smeared on the face to improve one’s skin complexion.

Staghorn sumac (Rhus typhina) is also very common in Wisconsin and has multiple uses. The red cob-like forms are its fruits, which can be stirred in water to make a beverage rich in malic acid (the one in apples) and citric acid. Mangos are in the same Cashew-nut family. “I have maybe 300 medicinal recipes recorded from 50 different recorders,” Lee told us. For example, it is nearly as anti-inflammatory as hydrocortisone. The shoots of the staghorn sumac can be peeled and eaten raw. All parts of the plant can be used both for natural dyes and as a mordant, or dye fixative.

Not to be confused with staghorn sumac, Lee is pointing out poison sumac (Toxicodendron vernix), aka swamp sumac, which is common in the bog. The resins contained in all parts of this plant, not just the leaves, cause skin irritations similar to but often worse than poison ivy. Breathing smoke from burning poison sumac can be life-threatening.

The Ojibwa word for tamarack (Larix laricina) is Mashkiiwaatig, which means “bog tree.” Indians mostly use the inner bark, the roots, the wood, or the pitch. Medicinally good for healing wounds and cuts. Roots can be used for stitching up birch containers.

Lee is grinding the root of a bloodroot plant with the haft of his knife (normally done with a stone). The resulting mash can be used for red dye or paint. Ojibwa and Potawatomi peoples also squeeze the juice into maple sugar and suck on it for sore throats.

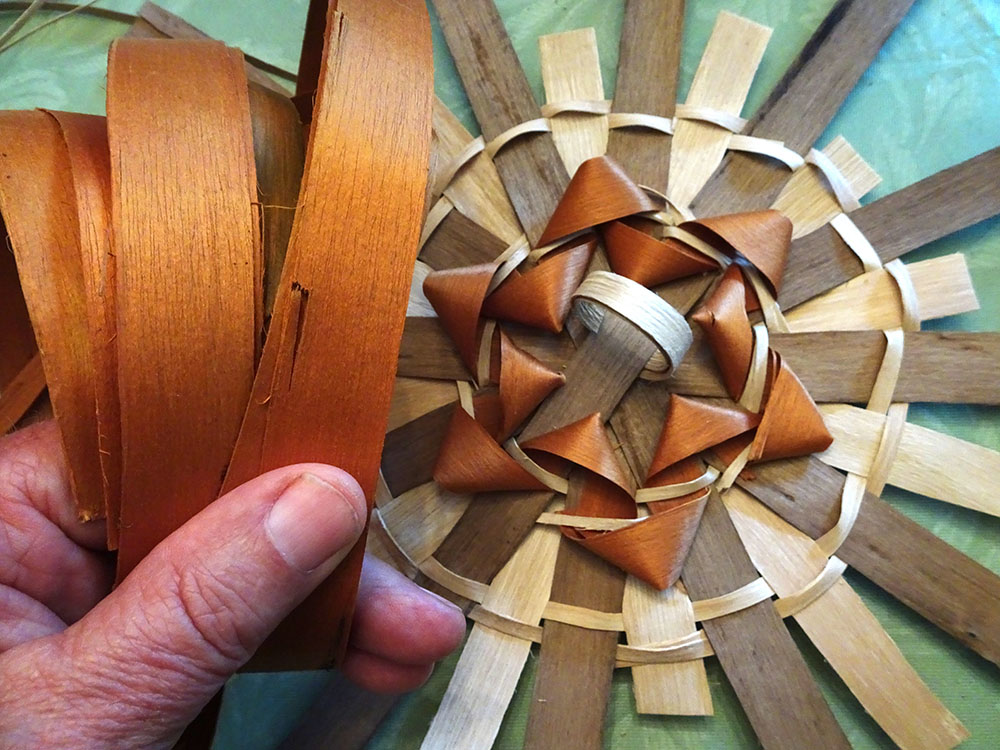

After pounding the surface of this ash log, Lee separates layers of wood to be used as splints in basketry. Later both sides of these splints are shaved in order to smooth them in preparation for dying. Then they are separated by pulling the single layer apart and splitting it into two equal halves.

Monarda, aka bee balm, is very common in Wisconsin. The Stockbridge and the Oneida both call Monarda “#6” probably for the number of its medicinal uses. It’s a mint with many terpenoids, so used for colds, sinuses, congestion, headache, antibacterial, etc.

Lee demonstrating how to separate strands of basswood fibers for making string and cords, which can be used for weavings and many other uses. The edible basswood buds and young leaves also were used for soups.

Broadleaf arrowhead was a main food for all tribes, as well as for muskrats, ducks and swans. The corms, which grow underground like tubers, are used like a potato, hence a common name in English is Duck Potatoes. Algonquian tribes call it Swan Potatoes (variant spellings of Wabasiipin).

Swamp milkweed, aka rose milkweed, rose milkflower, swamp silkweed, or white Indian hemp. As the name implies, it grows in damp or wet places like the bog. In Ojibwa the name zesab means string. Historically, its fibers, which are stronger than basswood and ten times as strong as cotton thread, were used in weavings, fishlines, bowstrings and fire bow cords.

Lee Olsen’s devotion to ethnobotany goes beyond acquiring knowledge and skills about these plants we found in the bog. He is a collector as well. He brought along a small selection of the hundreds of native artifacts that he has in his collection. Here is sampling of those he shared with the group.

Examples of naturally dyed yarns and mordant effects. Mulberries with copper mordant makes green; the same mulberries with a pinch of tin salt makes purple. Mordants may also be hardwood ashes, oak bark, acidic berries, different muds, clays, or crushed ores.

“In everything I brought I wanted to introduce some of the technology in native crafts—to demonstrate that they are not crudely assembled products.” ~ Lee Olsen.

For more information about Cedarburg Bog State Natural Area go to our Find-a-Park page.

Related stories:

A Walk in the Wilderness of Cedarburg Bog!

Butterflies, Dragonflies and Damselflies at Cedarburg Bog

A winter walk in the Cedarburg Bog

Lee Olsen grew up on Menominee land and began photographing and classifying flowers as a teenager. He learned taxidermy and established a museum. He majored in biology in college, keeping up on all those interests. He spent 39 years in Cedarburg as a middle school science teacher, where he kept a school nature museum. He also taught Native American Ethnobotany at UW-Milwaukee 1977-1990. He compiled a dictionary of Michigan Ottawa, collected Great Lakes native artifacts, collected an ethnobotany & native language library. His Master’s degree in Anthropology specialized in paleoethnobotany. Lee’s classes and walks are offered through the Friends of the Cedarburg Bog.

All photos by Eddee Daniel except as noted. Eddee Daniel is a board member of Preserve Our Parks.

2 thoughts on "Making Ethnobotany Exciting at Cedarburg Bog!"

Comments are closed.

I would have found this tour fascinating. How are tours of this kind publicized? Are you aware of the HO-Chunk black ash basketry currently on exhibit at the Museum of Wisconsin Art?

Thanks. They are publicized on the Friends of Cedarburg Bog website. Yes, I hope to get to MOWA soon.