BioBlitz! Observing nature—and humans—at Mequon Nature Preserve!

June 28, 2024 | Topics: Events, Places, Spotlight

By Eddee Daniel

Day 1

An air horn blast announces the start of the action promptly at 3:00 pm on Friday, June 21. The race is on! Scientists, master naturalists, museum and nature preserve staffers, biology educators, interns and other eager volunteers from many walks of life head out from the Education Center and spread out across over 500 acres of the Mequon Nature Preserve. Their mission: Count as many species of plants, animals, insects, fungi and anything else they can find in 24 hours.

My mission is to capture as much of the action as I can with my camera. It seems a daunting task considering there is no map showing where everyone is going and I am unlikely to find them by wandering randomly. I begin by tagging along with a team led by Mark Evans, a veteran naturalist and insect collector. A convoy of two ATVs and a golf cart takes us deep into a section of the preserve I’ve never seen before, near the mysteriously named Dohman Hidden Wetland.

We walk past three previously installed insect traps to where Evans wants to install a fourth trap. Each works differently in order to attract and capture as many distinct kinds of insects as possible. Evans goes right to work assembling a battery-powered light trap in the shelter of a small tree. Except for the UV light and waterproofed batteries, the whole thing is decidedly low-tech, as he explains, made largely from scrounged materials such as discarded plastic bottles. He suspends a sheet of plastic over the top to protect it from rain, which is in the forecast. As he works he maintains a lively patter with the rest of us, proving not only knowledgeable but quite patient with those of us, particularly me, who know little about any of it. This trap, he says, is intended for night-flying insects attracted by ultraviolet light, such as moths and beetles.

We then move to the other traps to collect what has turned up. The largest one, called a malaise trap, looks like a rickety, asymmetrical pup tent made of some sheer material, topped by a tube leading into an inverted plastic jug. Insects fly into the tent from the open underside and up towards the light of the sky only to be trapped in the jug. Evans empties the jug into jars, revealing quite a variety of bugs. Next, we stop at a small, homemade wire contraption known as a carrion trap because of its bait: In this case it is an unlucky mouse caught, Evans tells us, in his house with a traditional mousetrap. When insects attracted to its corpse fall or land below the trap they end up in a tray full of alcohol, creating new corpses that Evans and his assistants collect and identify.

By this time the western sky is darkening considerably. Not wanting to be caught quite so far out in the field, I leave the team still sorting and saving their collections into jars and head back in the direction of the Center, hoping to come across more surveyors on the way. Luck is with me. About halfway back I spot two people swinging nets around in the ecotone along the edge of the restored prairie (seen in the banner image at the top). I wade through the tall grasses and wildflowers, which seem to get deeper and deeper like an incoming tide, until I near them.

They introduce themselves as Brandon and Annika, museum volunteers. They are on the hunt for tiger moths, which, Brandon explains, co-evolved with bats. The moths’ consequent adaptation was to produce acoustic “clicks” to disrupt the predatory bats’ echolocation, thus avoid being caught. Brandon proudly holds up a jar holding Virginia Ctenucha moths, one of the most abundant of the tiger moths. I would have gladly continued the conversation, but the sky chooses that moment to start sprinkling. I hurry back to the large tent set up in the parking lot expressly for the event.

The Milwaukee Public Museum (MPM) organizes the annual BioBlitz, which is in its ninth year. It is held at different locations each year. In addition to the science of identifying and cataloguing species, which helps the host organization and others with ecological and conservation planning, the BioBlitz is intended to raise public awareness of the variety of life that exists locally, such as in neighborhood parks and natural areas, and the ways in which these various species improve the quality of our lives. It is also intended to be festive, educational, and just plain fun. Half of the tent I’m sheltering in from the rain is filled with tables loaded with microscopes and other scientific equipment for the surveyors to work with. The other half is filled with tables for entertaining and learning activities geared towards all ages. But I’m getting ahead of myself; that’s for Saturday. Many of the surveyors will continue their searching until dark despite the rain and some will work through the night. Not me. I’ll be back though, hoping the forecast, which is for more rain, is wrong.

Day 2

It is not wrong. I arrive early on Saturday morning, before the public activities begin at 10:00 am. Already there is a light drizzle, but I immediately hop out of the car. There is action right here in front of the Center. A figure draped in a black raincoat is hunched over a net next to the small pond adjacent to the parking lot. I peer into the recesses of the net but can’t distinguish any of the bits of organic matter there. The figure, Caleb Duren, an intern with Mequon Nature Preserve, glances up from his catch and happily tells me it includes fingernail clams, dragonfly nymphs, and aquatic beetles. You don’t have to go far afield to find biodiversity in the urban wilderness!

At 10:00 am, when the public festivities officially begin, there is already a line of people waiting in the rain for a guided tour. It is a birding tour, led by Rita Flores Wiskowski, a member of a BIPOC birding group. If you are a birder you already know that a birding hike involves more standing around listening and looking through binoculars than actual hiking. So, I am able to catch a bit of their action while also wandering away periodically to see what else I can find. I have no trouble catching up! In fact, I make it to the Observation Tower well before they do and see them in the distance progressing slowly across the prairie, tabulating their bird species.

The spectacular views from the Tower are the best way to get a sense of the scale of this remarkable preserve. Twenty-five years ago most of its 510 acres was agricultural cropland. After two decades of habitat restoration efforts you can now look out over broad prairies dimpled with wetlands and punctuated with hardwood forests. The laudable vision of Mequon Nature Preserve is to restore the land to pre-European settlement conditions “with reverence and conviction,” while enriching the lives of visitors with opportunities for environmental education and recreation. The BioBlitz is a perfect match with its mission!

I descend, make my way across a large wetland known as Paul’s Pond and into one of the forests: Charlie’s Woodlot. The rain eases up as I enter the sheltering canopy. I catch up with another guided tour. Mariah Rogers, a mycology expert, is helping a group of visitors find and identify fungi. They are standing next to the most fascinating and wondrous example I’ve ever seen: a fairy ring! These occur naturally in the wild and can be any one of a number of different fungi; in this case Crown-tipped Coral Fungi.

Deep in the forest I spot a bright pink jacket; I head towards it. A gray jacket resolves out of the mist next to the pink one as I approach. The jackets turn out to be worn by the husband and wife team of LeRoy and Anne Gehring, members of the Wisconsin Mycological Society. When I ask if they’ve found anything of interest they reach eagerly into bags and pockets. He produces a Jelly Fungus and she the evocatively named Dead Man’s Fingers. Before they can show me more a heavier rain begins to penetrate the canopy overhead. I wave goodbye and run to find a tree with a denser crown to hunker down under until it slows.

I am amazed. By many things. First of all, I’m amazed by the dedication and determination of the many surveyors I’ve come across. Not only are they universally devoted to the task at hand, but they are totally welcoming when approached by a perfect stranger and happy to impart the knowledge gleaned in their forays. I am further amazed by the numbers of other people, especially families with children of all ages, who have come out to experience the BioBlitz and stayed out during fitful bouts of rainfall. I have to hope it’s due to a craving for a deeper connection with nature, as well as to instill in the next generation a love of scientific inquiry and studying the intricacies of the natural world.

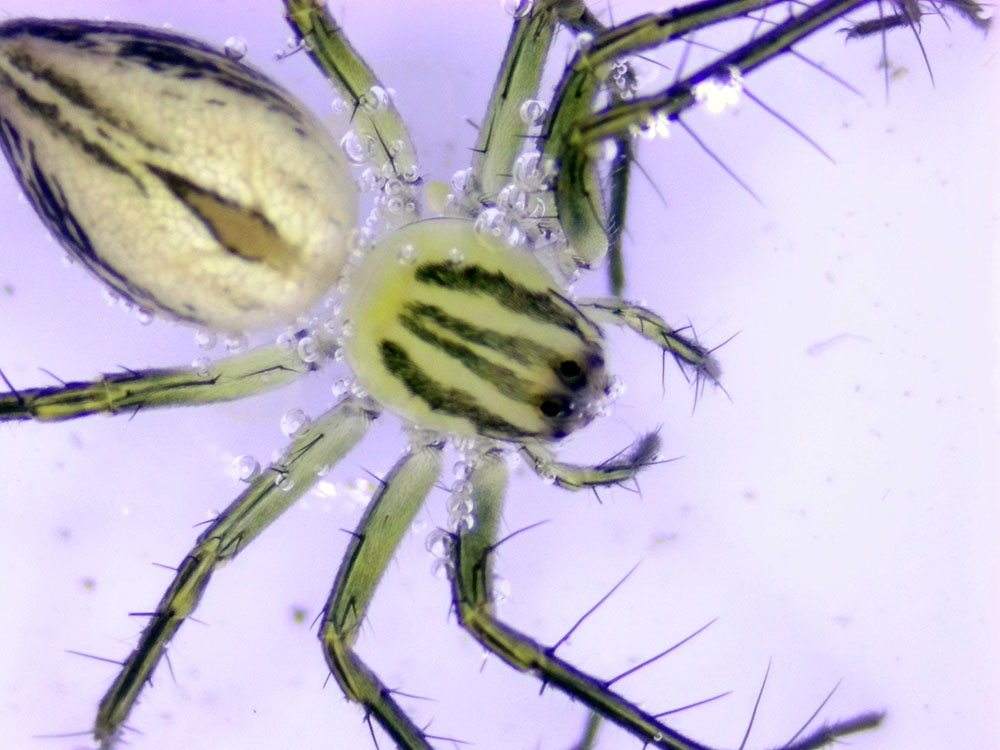

Back in the tent, I am further amazed by the sheer numbers of creatures and plants that have so far been assembled, placed under microscopes, identified, and catalogued. Many more have been photographed or simply listed on bird counts. John Dobyns, a biology professor and MPM Research Associate, graciously allows me to take a peek through his microscope at a spider, which looks small and benign on the tray but prickly and menacing when enlarged in the lens.

Mark Evans has come in from the rain. I find him at his station hidden behind magnification glasses. He is “field pinning” moths with insect pins so that they can be handled without damaging them. This is one method, he explains, of protecting specimens for transport to the lab where they can be dried, moved to museum drawers, and identified; or later “spread” and stored for the long term in the museum’s collection.

On the other side of the tent I mingle with people engaged in activities like how to press plants—participants get to take home a simple plant press—keeping and illustrating a nature journal, and matching pictures of caterpillars with pictures of their respective butterfly or moth. That looked very hard at first, but I was able to match all but one—with a little help!

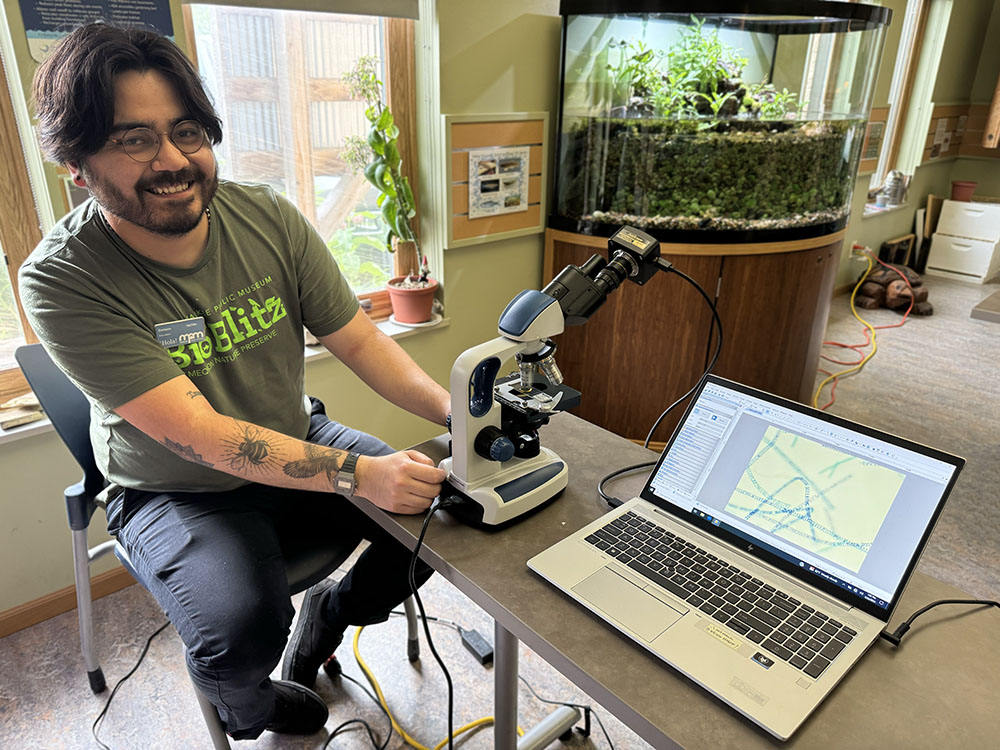

Some of the action is taking place inside the PieperPower Education Center. In one of the classrooms I find Emiliano Rodriguez, MPM Outreach Educator at one of several stations intended to teach visitors about microorganisms and invertebrates living in pond water. Rodriguez explains the process. Water collected from one of the preserve’s many ponds was placed in a tank. Microscope stations allow guests could view the water. Two special dissection microscopes enable guests to look at the pond water on a petrie dish to get a closer look at microorganisms swimming around. Because some of the species that affect our daily lives are too small for the naked eye to see!

If you’re curious about the specifics of what the surveyors observed during their twenty-four hours, which ended up totaling close to 1,000 distinct species (according to the museum’s preliminary reporting), they have been recorded at iNaturalist.org. Those species included Plants: 309; Amphibians and Reptiles: 5; Birds: 76; Fishes: 3; Mammals: 11; Fungi & Lichen: 113; Spiders: 32; Insects: 416; and other Invertebrates: 22.

As important as those numbers are, they are not the primary reason for doing a BioBlitz. In a museum press release, MPM President & CEO Dr. Ellen Censky put it this way:

“Learning about nature is the first step toward conserving nature. Through the many educational activities offered at BioBlitz, along with the chance to engage with scientists, we hope to foster wonder and appreciation for our natural world, and ultimately, inspire community members to do their part to help protect the environment for the future.”

For more information about Mequon Nature Preserve go to our Find-a-Park page.

Related (Mequon Nature Preserve) stories:

Mequon Nature Preserve: Frolickers out in force!

Kristin Gjerdset: Artist in Residence at Mequon Nature Preserve

Monarch butterfly tagging at Mequon Nature Preserve

Meet Tilia: Canine conservation ambassador at Mequon Nature Preserve

Snowbirds at Mequon Nature Preserve

Related (scientific observation) stories:

Snakes alive! Citizen Science snake surveys at Retzer Nature Center

Wetland Monitoring: Citizen scientists join in the fun!

Hawk Watch at Forest Beach Migratory Preserve

Downer Woods: A connection to nature at UWM

All images by Eddee Daniel except as noted. Eddee Daniel is a board member of Preserve Our Parks. Mequon Nature Preserve is a project partner of A Wealth of Nature.

One thought on "BioBlitz! Observing nature—and humans—at Mequon Nature Preserve! "

Comments are closed.

What a great article, Eddee! Really enjoyed your pictures and narrative – no wonder you were so excited about it! Glad this happens on a yearly basis – so much to learn!