Competing views on Kletzsch Park project proposal

January 21, 2019 | Topics: Issues

Editor’s note: A public hearing was held on Jan. 9 at Glen Hills Middle School in Glendale to unveil a proposal to create a fish passage in Kletszch Park that would enable fish to migrate around the dam there. You can read a report on the hearing and the proposal in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. The proposal that was presented showed a single design solution and suggested that there were no viable alternatives. This argument is a reaction to that proposal. Preserve Our Parks has not taken a stand on these alternative proposals.

Arguments Against the Current Kletzsch Park Project Proposal

By Martha Bergland and Jim Uhrinak

First, we are for installing a fish passage in the river channel or around the dam on the east side. We are not suggesting that the dam be removed. However, there are strong reasons to reject the current fish passage and viewer platform proposal prepared for the Milwaukee County Parks (contacts listed below).

The Trees.

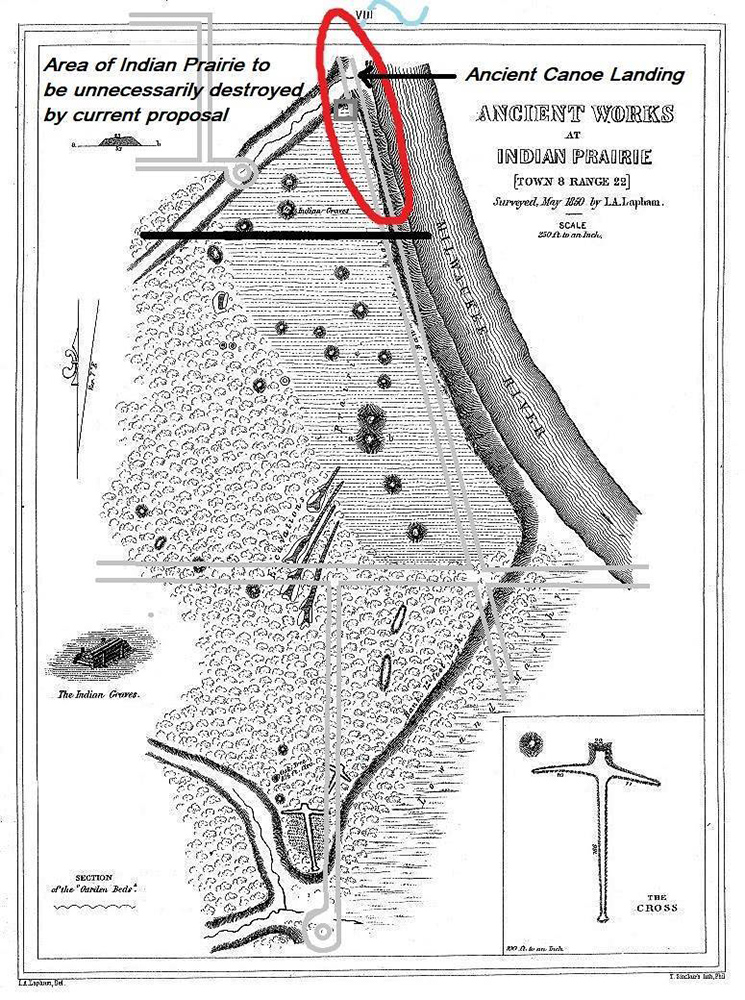

The proposed removal of six old oak trees is a needless destruction of a natural element on this site as valuable as the river. This set of oak trees is the savanna fringe of Indian Prairie recorded in this place by Increase Lapham in 1850 (see map below). Do we really have so little imagination and foresight, time or money that we have to destroy these ancient living beings and the bluff they stand on when there are other possibilities for the fish passage? Would we really rather have a hard-edged party platform with a view across a ditch than these irreplaceable open-grown oaks?

We are asking that what Aldo Leopold called an “ecological conscience” be brought to bear in redirecting the fish passage proposal. Presenting this current plan as if there is a forced choice between the trees and the fish passage is wrong. Intelligent and imaginative engineering plans can be made not at the expense of, but in the service of nature. Aldo Leopold asks us to not be “intimidated by the argument that a right action is impossible because it does not yield maximum profits.” The wrong action, Leopold continues, “is not to be condoned because it pays.”[1] We are all citizens, Leopold tells us, of the land-community, as are the trees and the fish.

Not only are the trees an essential part of the natural system, but without the trees, the mysterious and romantic character of the dam overlook is destroyed. One of the reasons we are drawn to this spot and to others in the natural world (and to well-designed gardens) is that we find there a sense of mystery and of romance because all is not revealed at once. We delight in discovery. Even though we may not be aware of it, when we come along the Milwaukee River Parkway and see those old oaks we know we have arrived at a place different from any other place in the city and perhaps the county. Those craggy trees ceremonially preside as we slow and stop and get out of the car or walk into their shade at the edge of the bluff. Beyond the trees we glimpse patterns of light and shade, the sheen of sunlight on the pool above the dam and foaming energy of the river. Perhaps without realizing it, we are drawn as much by the trees to this place as by the river. Trees like these are rare in our urban and suburban lives, as rare as rivers.

The History.

The proposed complete destruction of the bluff disregards the history of Indian Prairie. In 1850 Wisconsin’s pioneer scientist, Increase A. Lapham, surveyed this site, then called Indian Prairie, an Indian earth-mound ceremonial complex, recorded in his most important work, Antiquities of Wisconsin as Surveyed and Described. Though this site lives in the popular imagination as one of Wisconsin’s great cultural landscapes, conventional archaeologists have long considered Lapham’s Indian Prairie as obliterated. Yet this past year, previously unrecognized mounds have been identified through research by Milwaukee Audubon Society and the Wisconsin Effigy Mounds Initiative. A magnetic-gradiometer survey may allow us to precisely locate buried intaglios and lost earth mounds in the area. It is likely that the several intaglios or excavated mound forms that Lapham documented were simply filled and it may be possible to recover parts of them. This is significant because to date only one known effigy intaglio has survived in the entire state of Wisconsin.

Just as Indian mound builders a thousand years ago looked from their ceremonial mounds and burial places out across the river bluff to the river, so can any modern pedestrian walking along the bluff develop an authentic sense of place at this site. Since the river bank and bluff are essentially where they were in 1850 and possibly a thousand years ago, it seems presumptuous for modern engineers to propose tearing the whole bluff away as an “improvement.” Straight (skateboard) ramps, additional paved sidewalks, and retention walls might not contribute to the present peaceful and naturalized condition of the bluff. A finer aesthetic is found when human use integrates with history as well as with natural beauty.

The Alternatives.

We agree that the stated objective of creating fish passage will help to restore watershed health by improving biodiversity and bringing an important food base to the entire ecological system. But other options would allow fish passage while retaining most of the character of this special place.

Although there are several possible alternatives, an east-bank fish passage solution could satisfy all concerns. This would mean lower overall costs, efficiencies for fish passage, and other civic benefits. The week of January 25th, Milwaukee Audubon Society and the Glendale Natural Heritage Committee are exploring options that may satisfy engineering concerns and make an east bank solution possible by unifying public and private interests.

When we consider the time scales this part of the Milwaukee River and its trees have seen, we cannot let time-limited grant money burning a hole in our collective pockets and the desires of destructive development forces undermine better solutions. Slowing the process to allow us to better understand historical and prehistorical uses of the important place seems to be the better part of wisdom. Cutting down old oak trees and moving a bluff can never be undone.

To use the terminology of Preserve Our Parks, why would public leaders squander our wealth of nature rather than pursue unnecessary cut-and-fill development of Kletzsch Park’s natural and historical crown jewel?

To comment, contact District 1 Representative and County Board Chair, Theodore Lipscomb, theodore.lipscomb@milwaukeecountywi.gov, 414-278-4280. Karl Stave, Kletzsch Park Dam Project Manager, 414-278-4863. Therese Gripentrog, County Parks Representative to the Development Team, 414-257-6242.

UPDATE: A fish passage was completed in 2023 on private land across the river from Kletzsch Park.

Note: [1] Aldo Leopold quoted in Curt Meine, Aldo Leopold: His Life and Work (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 2010), 499-500.

Martha Bergland is the author, with Paul Hayes, of Studying Wisconsin: A Life of Increase Lapham (2014). Jim Uhrinak, consulting arborist and land restorationist, Milwaukee Audubon Society board member, writes and speaks on cultural landscapes of the Midwest. They live in Glendale. Photos by Susan Ruggles. Formerly an MATC staff photographer, Ruggles now photographs the peace, social justice, environmental, and women’s movements in Milwaukee and statewide.