Andrew Musil: Artist in residence at Cedarburg Environmental Study Area

July 5, 2019 | Topics: featured artist

Andrew Musil is one of 12 artists participating in a year-long residency program called ARTservancy, a collaboration between Gallery 224 in Port Washington and the Ozaukee Washington Land Trust. Each artist has selected an OWLT preserve to spend time in and to engage with. To read more about the artist in residency program, click here.

Artist statement by Andrew Musil

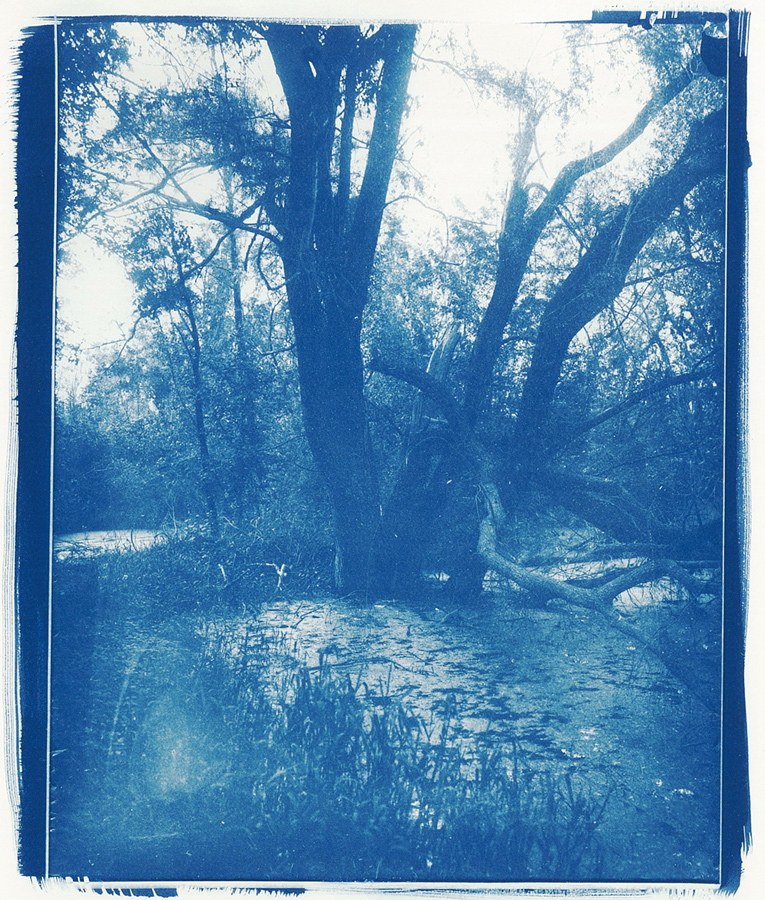

I was attracted to the Cedarburg Environmental Study Area (CESA) because of its history. CESA was farmland until the Senglaub family restored its former wetlands and planted over 40,000 trees. Reflecting on photography’s well-established relationship with “un-defiled” or “virgin” nature, I was interested in photographing this site—which by contrast has undergone such transformations—with appropriately historic processes.

I used CESA for my research. But instead of studying its specific habitats, I used it for the practical research of analog (traditional, non-digital) photography, creating my own light sensitive papers and glass plates. The experience has taught me an understanding of these methods that go beyond the instructional texts.

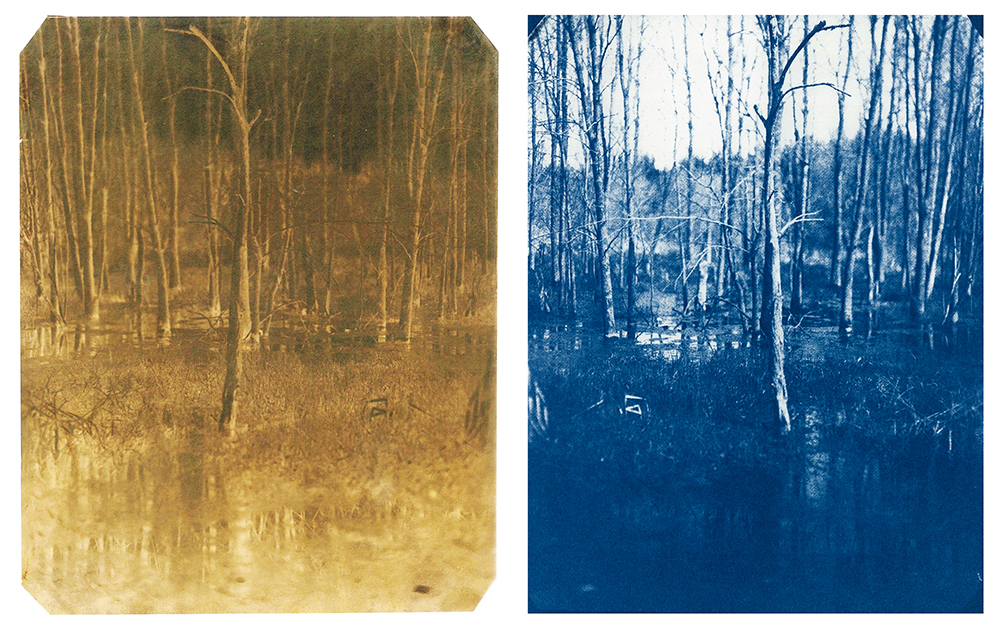

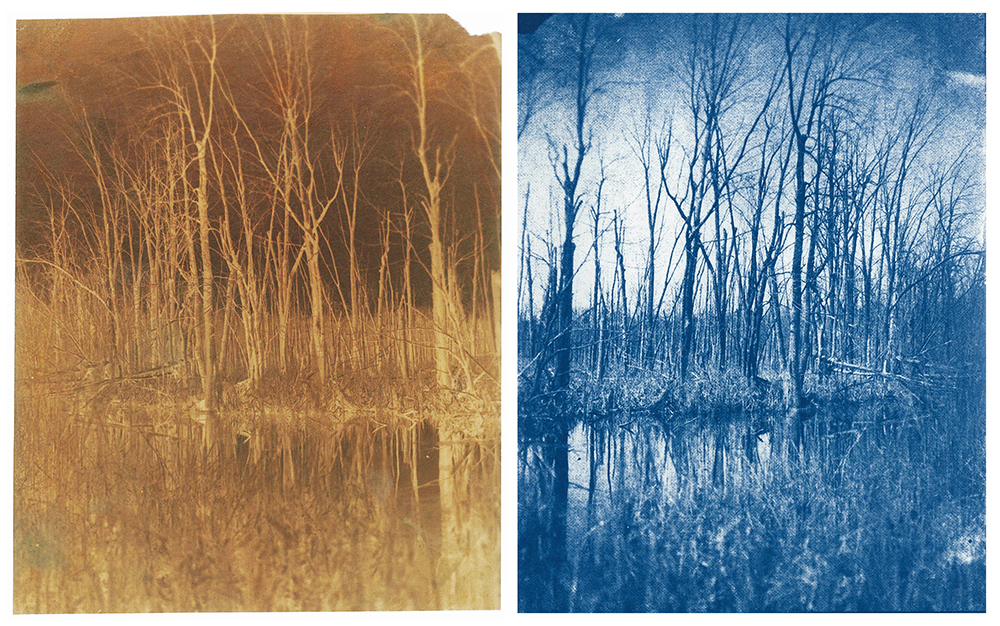

I chose to use a process known as the calotype. The calotype was amongst the earliest photograph processes. It was invented by William Henry Fox Talbot in the 1830s and utilized throughout the 1840s.

Here is an explanation of the process: A plate is prepared by floating a thin sheet of paper on solutions of silver nitrate and potassium iodide to create a light sensitive film of silver iodide. After exposing the paper to ultraviolet light, it is then submerged in a bath of gallic acid which transforms what is known as the latent image into a visible one. Areas that received the most light exposure become the darkest parts of the resulting image, which is why it is known as a negative (or reversed) image.

The remaining light sensitive silver iodide is then dissolved in a solution of sodium thiosulfate so the calotype can be further exposed to light without darkening. This allows for the calotype to be reversed (or printed) by placing another light sensitive paper (such as cyanotype papers) behind the negative and exposing it to bright light. In this process, the traditional dim, red-lit darkroom is replaced by bright blue skies to photograph under.

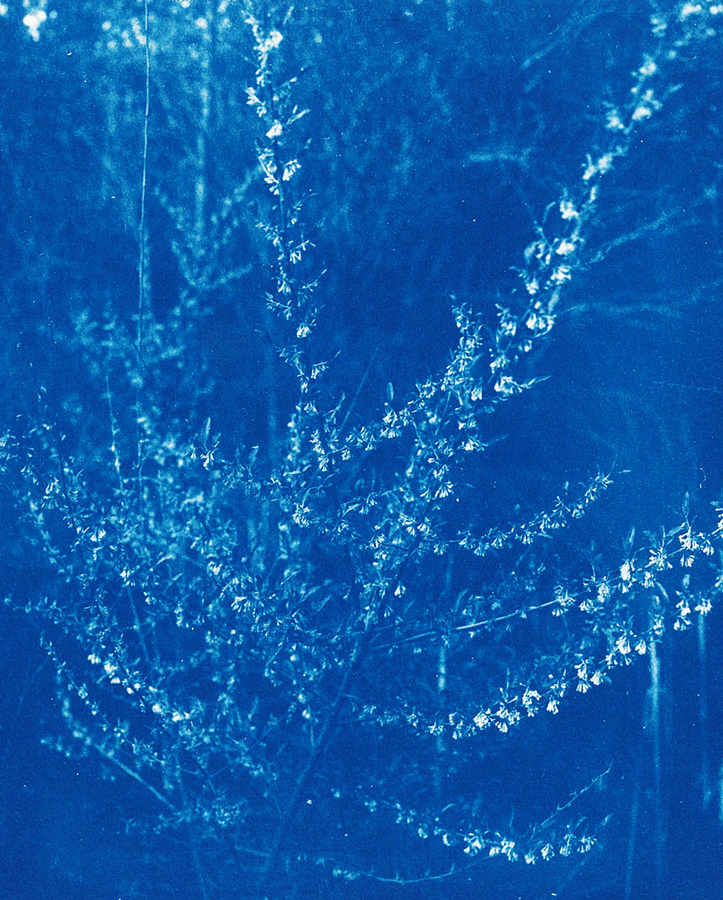

In the field, concentration on minute details may be overlooked when looking for potential photographs. One may wander, drift, listen, and intuit one’s own inspiration. This kind of listening broadly to nearby happenstances is unlike for listening for practical purposes (e.g., for a timer’s click at the end its countdown). These are things of which I was previously oblivious—before the hours spent under the sun pursuing a purposeless purpose: art.

From this experience I have a new understanding of what photographer Gary Winogrand meant when he said he was “photographing to find out what something will look like photographed.” Calotypes do not render their scenes the way we see them. Because they are sensitive only to ultraviolet light, they need lengthy exposures. They also incorporate the paper texture within the printed image.

Modern films may act in a similar manner, to create images that our eyes cannot see. (I also photographed with a 35mm camera during the long calotype exposures.) I found myself looking for scenes that I could not see without the camera, in order to discover the photograph after it is processed.

After returning to CESA many times, I could reflect on my documentation of a place undergoing constant change. In a matter of weeks an exact spot would look entirely different. This experience, a gift really, became meaningful in more ways than I can try to define. I am grateful for the opportunity to contribute to the ARTservancy project. The experience provided a gift of space and time to reflect upon my research and practice.

GALLERY

BIO

Andrew Musil earned his BS in Printmaking at the University of Wisconsin, La Crosse in 2014 and his MFA in the Photography and Integrated Media Program at Ohio University in 2018. His projects explore relationships of technologies and their users, and the effects of innovation. His practice combines contemporary media with antiquated photographic and printmaking processes. His work has been exhibited in museums and galleries nationally.

This is the latest is a series of featured artists in The Natural Realm, which is intended to showcase the work of photographers, artists, writers and other creative individuals in our community whose subjects or themes relate in some broad sense to nature, urban nature, people in nature, etc. To see a list of previously featured artists, click here. An exhibit of the work of ARTservancy artists in residence is scheduled to open at Gallery 224 on September 13, 2019.

All images courtesy of the artist, except as noted.