Two perspectives: Kletzsch Park River Access & Fish Passage Project

December 4, 2019 | Topics: Issues

Edited by Eddee Daniel

The current plans for the Kletzsch Park River Access & Fish Passage Project will be discussed at a meeting of the Parks, Energy and Environment Committee of the Milwaukee County Board on Tuesday, Dec. 10.

Meeting time: 1 p.m.

Location: Milwaukee County Courthouse, Room 201B.

This project generated considerable controversy and public outcry when plans were first unveiled in January of this year. Those original plans would have obliterated a stand of mature oak trees along with a substantial portion of the bluff overlooking the dam. New plans have been drawn up that attempt to address the public’s concerns. Those plans can be seen on the Milwaukee County Parks website.

Two prominent stakeholders in this issue, Milwaukee Riverkeeper and Milwaukee Audubon Society, have differing views on the new proposal. Here are their positions in their own words.

What’s the Big Dam Deal?

By Cheryl Nenn, Milwaukee Riverkeeper

At Milwaukee Riverkeeper, we pride ourselves on being the voice of the rivers. And if Milwaukee’s rivers could talk, they would probably SCREAM, “let us flow free.” As river protectors, we take our job seriously to ensure our shared resource will be swimmable, fishable and drinkable for our children and our children’s children. We are at a pivotal moment in the history of water in Milwaukee. Momentum and energy is building to prioritize the work to clean up historically contaminated parts of our rivers and Estuary through EPA’s Area of Concern program. This could mean a serious federal investment to achieve cleaner rivers and healthier communities.

The proposed fish passage in Kletzsch Park is a generational opportunity to move native fish upstream from Lake Michigan past the LAST man-made barrier to their passage in Milwaukee County, the Kletzsch Dam. Many of our native fish can’t jump over barriers, and can’t swim upstream through intense flows created by dams and other obstructions. In addition, many native fish, such as northern pike, require access to vegetated wetlands for spawning, few of which exist along the Milwaukee River in Milwaukee County. Allowing fish to reach high quality spawning habitat upstream is essential to improve the health and viability of our fish populations.

Providing a fish passage structure at Kletzsch Dam also provides connectivity to the significant restoration work and improvements made upstream by the Ozaukee County Fish Passage Program, which has removed several major dams, built a fish passage around the Mequon-Thiensville Dam, and addressed hundreds of smaller fish passage barriers. This type of river restoration opportunity does not present itself often, and it is rare that scientists, elected officials, government agencies, community groups, AND funding sources all come together around a project –we may not get this chance again.

Milwaukee Riverkeeper is committed to a vision of free flowing rivers, and was the main proponent to remove the Estabrook Dam, which was finally removed in spring of 2018 following a decade long fight. We have also advocated for the removal of 10+ other dams in the Milwaukee River Watershed. Many have questioned why we aren’t lobbying for removal of the Kletzsch Dam. We agree that dam removal would be our first choice to addressing this fish passage impediment, and would likely be the most effective and cheapest option. However, one of the lessons we have learned in nearly 25 years of this work, is that achieving community consensus usually means compromise – there is often not a clear winner and all sides don’t get everything they want. While providing a fish passage around the dam would not fully restore the natural ecology to the river, it would allow us to retain the “Kletzsch Falls” that many in the community love, while still achieving our vision of FISHABLE rivers for everyone.

If we do not grasp this opportunity and move forward, we will lose more than just fish passage – we’ll also miss out on another important opportunity to connect more folks to our river through an improved portage, access points, and accessible paths. This will not only protect paddlers, fishermen, and other river users, but will ensure that ALL community members can recreate in our parks and enjoy our rivers safely. After all, who actually owns our rivers? We all do.

Indian Prairie is worth preserving

By Peter Thornquist, Milwaukee Audubon Society

Milwaukee Audubon Society agrees with the goals of free-flowing waterways and passage of fish, but we believe that the construction proposed by Milwaukee County Parks at the site of the Kletzsch Park dam would be destructive to one of the few remaining natural bluffs overlooking the Milwaukee River. This area holds a rare remnant of oak savanna, and is located at the edge of a special area known since the first white settlement as “Indian Prairie,” a burial site held in reverence from ancient times until today.

Oak savannas are neither prairie nor woodland, but a mix of the two with scattered open growth oak trees, once covering fifty million acres of the Midwest. These savannas were the result of periodic burning by American Indians to maintain open and food-rich landscapes. They all but disappeared with white settlement, and are now considered by the Wisconsin DNR as “one of the rarest and most threatened plant communities in the world.” Only two remnant oak savanna fragments can be found in the greater Milwaukee area, at the Stahl-Conrad homestead in Hales Corners, and at Indian Prairie. The Indian Prairie veteran trees are artifacts of American Indian burn practices and hold the potential for high quality site restoration.

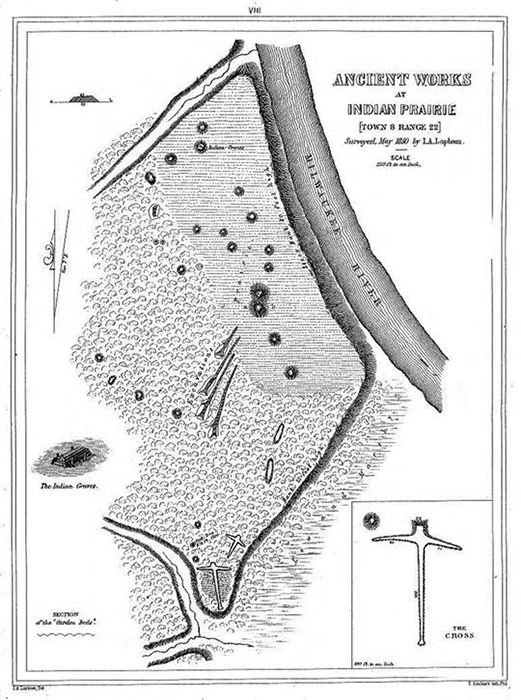

The Kletzsch Park oak savanna trees are part of the larger “cultural landscape,” an integration of nature and humankind, which reflects a long and intimate relationship between peoples and their natural environment. When Wisconsin’s first scientist and surveyor, Increase Lapham, visited this area in 1850, it was known as Indian Prairie, a vast complex of prehistoric American Indian earthworks. There were two large round mounds 53 feet in diameter, 20 smaller conical mounds, two large cross shaped mounds, and four panther “intaglios” meaning a silhouette excavation into the earth.

Although most of the earthworks were destroyed by white settlers, and the riverbank became the site of a mill, the place still holds many of the original attributes that made it one of Wisconsin’s great ceremonial centers.

The construction proposed by Milwaukee County Parks for an in-stream fish passage through the Kletzsch Park dam, along with accompanying viewing stands, and canoe portage, would be destructive to this historic bluff. Three parallel rows of steel sheet pilings hammered into the ground, extending 400 feet above the dam, would be implanted along the base of the bluff. An access road large enough for a construction equipment would extend down the bluff then along the edge of the river. Although this proposal was designed to spare the oak trees, the disturbance to the root systems will dramatically shorten the lives of these ancient trees older than the state of Wisconsin.

Just north of the project area is another ancient site called “Spring Grove” that once had three Indian mounds, one of which remains. The entire bluff along the riverbank was a continuum of sacred places, and should be preserved as a gem of our natural heritage. We consider any further construction along the bluff of Indian Prairie destructive of our commonwealth’s cultural landscape legacy, and a beautiful, healing part of our natural heritage.

Related story: Competing views on Kletzsch Park project proposal (Jan 2019)

UPDATE: A fish passage was completed in 2023 on private land across the river from Kletzsch Park.

Cheryl Nenn is the Milwaukee Riverkeeper.

Peter Thornquist is on the board of Milwaukee Audubon Society.

Editor’s note: Cheryl Nenn is also on the board of Preserve Our Parks. However, her views represent those of Milwaukee Riverkeeper. Preserve Our Parks has not taken a position on this project.

Featured image of Kletzsch Park Dam by Susan Ruggles.