Jackson Marsh Wildlife Area: Degrees of Wilderness … and Solitude

January 18, 2022 | Topics: Places, Stories

Story and photos by Eddee Daniel

Warmed by the exertions of tramping through trackless snow and clambering over fallen trees, I pause. I scrape the cap of snow off a stretch of comfortably low log and sit. Slowly, I breathe in the crisp, cold air. I listen to the silence. Nothing rustles in the blanketed undergrowth. I strain to catch the sound of a bird calling, or flitting through the trees. Hearing none, I settle more deeply into a wilderness solitude. There is a certain satisfaction, for those of us who heed the call of the wild, in finding oneself alone in a place so clearly reserved for wildlife, even if none make an appearance. The wild, by definition, is unaccommodating. Few places in southeast Wisconsin are as wild as the middle of a swamp.

“There are degrees and kinds of solitude.”

So wrote Aldo Leopold in his classic A Sand County Almanac. I recently revisited Jackson Marsh Wildlife Area in search of, not so much solitude, as one of the kinds of places you’re likely to encounter it: wilderness. To my mind, there are degrees and kinds of wilderness. The middle of a 2,600-acre swamp is the kind where you’re likely to find a great degree of wilderness. The reason is simple: Almost no one wants to go there. There are good reasons for this, most of them having to do with water and mud.

That is why I like to walk in the swamp in January. Winter, lo and behold, makes it possible to walk on water. Possible, however, doesn’t necessarily mean easy. But before I take you into the swamp let me clarify some terms. The heart of the fairly vast Jackson Marsh Wildlife Area is a 590-acre portion known as the Jackson Swamp, which has the distinction of also being a designated State Natural Area. Overall, the Wildlife Area includes both marsh, which is wetland dominated by grassy vegetation such as cattails, and swamp, which is wetland dominated by trees.

The WDNR map of the Wildlife Area shows a total of 11 parking lots, most of which line the perimeter of the preserve. On this occasion, however, I choose the one closest to the center, off the only road (Hwy G) that bisects the property. I strike out due west, straight down a tunnel-like passage through the trees, which is perpendicular to the highway—evidence that the degree of wilderness is less than absolute. The purpose of this cleared pathway is not apparent and there is no visible trail. A single set of human prints, however, indicates I am not the first to pass this way since the last snowfall.

Right away I have to cross a frozen stream cutting through the slightly higher ground of the passage. The ice sinks under my weight, creaking a warning to remain vigilant: The frozen surfaces of the swamp may not be as sturdy as I’d hoped. As I said, it isn’t an easy walk. I proceed with caution, following the footsteps of my erstwhile predecessor, zig-zagging around and sometimes over brush, clumps of grass protruding from the snow, and numerous downed tree trunks. The swamp on either side of this raised ground, despite being semi-frozen, is far more impenetrable, with tangled undergrowth and frequent snarls of fallen trees—another degree of wilderness and one I’m not prepared to negotiate given the uncertainty of the ice.

Before long I reach an intersection. Hardly a term you expect to use when referring to a wilderness but I don’t know how else to describe it. Another cleared, straight tunnel-like passage, this one with a channel that is more ditch than creek running down the middle, at precise right angles to the one I’ve been following. Fortunately, I don’t have to test the ice on the channel, which is too wide to jump across. I cross on a new-looking footbridge (which, in fact, wasn’t here the last time I came).

I’ve been on the lookout for wildlife, so far with no luck. Suddenly, in the open sky of the intersection above me a great blue heron soars past. It is gone before I have the presence of mind to raise my camera. Its presence, here in January, is far more startling than the mere surprise of its appearance. Herons are migratory, requiring open water to feed. I’ve never before seen one in Wisconsin at this time of year. Is it yet another sign of climate change or just a confused (and hungry) bird?

The straight passage continues, narrower now and more choked with downfall. The boot prints I’ve been following also continue. I punch through the ice now and then, revealing the mud underneath as I draw up my boot. The splintered wooden supports of an old, hunter’s blind dangle in a tree just beyond the edge of the cleared passage. After a while there are no more footprints. I trudge on into another degree of solitude.

I don’t know how far I’d walked when I decided to sit and rest and soak up the silent solitude. Far enough to feel like it was the middle of nowhere. Little had changed in the scenery around me. If I had come for scenic views, I’d have been better off staying around the edges of the Wildlife Area, where most of the trails are located. As for the degree of wilderness, just when I thought I’d finally gotten into it as deep as possible (without leaving the relative comfort of the cleared passage), I came to a sign on a post. The sign announced that the land is privately owned with an easement allowing the public to enter and to hunt. A list of regulations followed. There’s no escaping it. We live in an age when the idea of “managed wilderness” is not an oxymoron but a necessity.

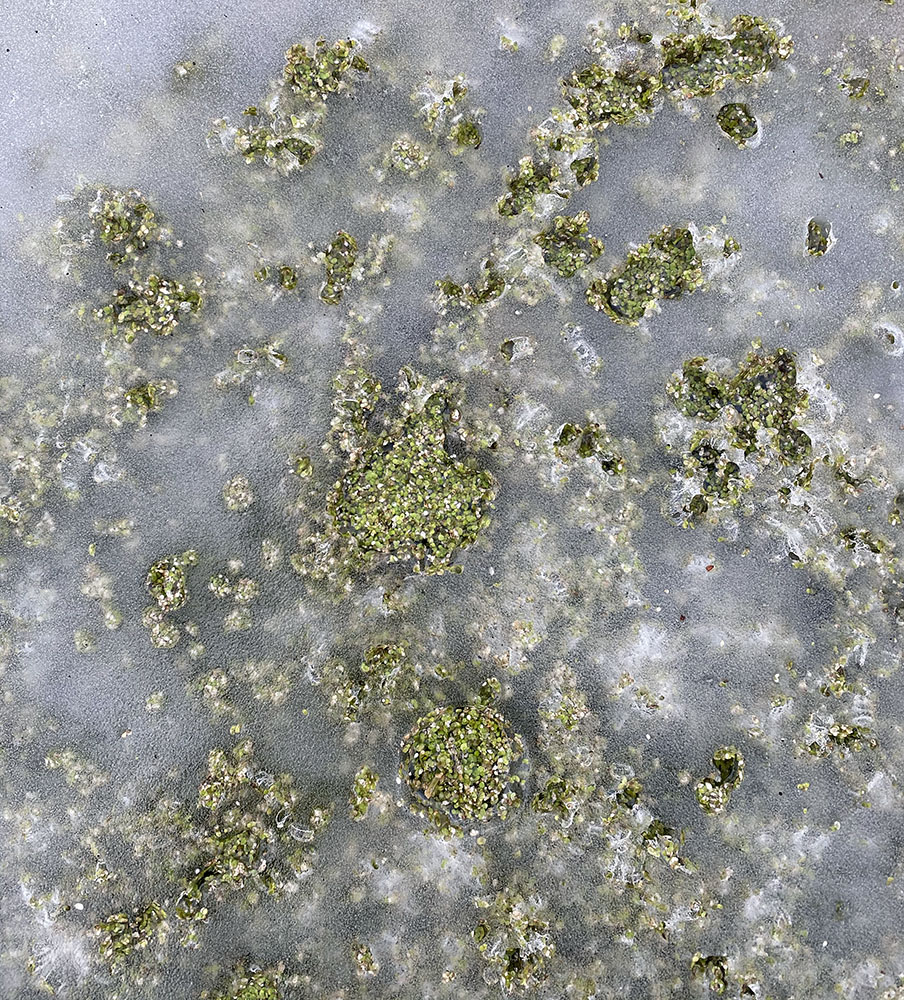

Undiscouraged, I turn around. In the first chapter of A Sand County Almanac, which is organized by months of the year, Leopold wrote of January that “observation can be almost as simple and peaceful as snow, and almost as continuous as cold.” As I make my way back to my car, I enjoy the peace and quiet, observing animal tracks, berries on bushes and trees, the texture of cedar, enormous exposed root balls of upended trees, the play of sunlight on a tapestry of bare branches …, and many more moments of transcendent if subtle beauty.

* * *

In addition to photographs shot during the outing described in the story above, I’m including a selection taken on previous forays in other seasons and different parts of the Wildlife Area.

For more information about Jackson Marsh Wildlife Area go to the Find-a-Park page on our website.

Related story: Jackson Marsh, a local wildlife area for all seasons.

Eddee Daniel is a board member of Preserve Our Parks and curator of The Natural Realm.