Foreign Correspondence: The Natural Realm in New Zealand

April 2, 2025 | Topics: Places, Stories

By Eddee Daniel

Kia Ora!

Our friends in Auckland greeted us at their home with open arms—and wide-open, screen-less doors and windows that allowed natural breezes free reign in the house. In fact, everywhere we went in New Zealand for the next three weeks, we saw no screens over any doors or windows. It seems a small thing now, compared to the overwhelmingly beautiful beaches and mountains. But that absence of screens was my first introduction to a society that is attuned to nature and simply values the clear views, unfiltered natural light, and aesthetic appeal more than the need for protection from insects. I had to wonder if no screens meant New Zealand has no mosquitoes, but an internet search confirmed that it does. Turns out, New Zealanders have a cultural preference for letting fresh air in rather than keeping bugs out. It seemed like a revelation!

This was just the first of many differences we discovered between the U.S. and New Zealand when it comes to the environment. Some of the differences were subtle, some stark. I don’t usually write about travel experiences in The Natural Realm but since the New Zealander culture seems so closely tied to appreciation for and care for the land—and the Earth—I expect it will interest you as much as it has me.

One particular delight for me and this blog A Wealth of Nature were the many urban gardens we encountered. Even in their cities, New Zealanders draw close to nature. Of course, Milwaukee and its excellent park system stand up well in this regard. But what we don’t have are giant trees. For example, one of the first things I noticed when I stepped into the Christchurch Botanic Gardens was an enormous beech with a trunk so massive that resembled a rock formation. Its broad, round, symmetrical canopy was equally immense. We have beeches in southeast Wisconsin, but I’ve never seen one this big.

That was just the beginning. As we walked the city’s garden the trees got bigger and bigger. There was a Monterey Cypress, several pine species, oaks, redwoods, even a number of sequoias—until we reached the biggest tree of them all. Yes, bigger than the sequoias (that at 150 years old are still young) was a eucalyptus species known as alpine ash. Its gargantuan trunk twisted as it rose upward, like a tornado. Unlike sequoias, redwoods and pines, the alpine ash also gets broader as it goes higher, with numerous large limbs spreading in all directions, making the tree appear even larger.

What really impressed me, though, were the many modest, small-town parks throughout New Zealand that also had gigantic trees. Somehow, 100–150 years ago, there must have been a collective effort to plant these trees in city/town parks, knowing they would grow into giants for future generations to enjoy (not unlike the visionary planners in Milwaukee during the same period who organized a park system along its rivers and lake).

After a few days of lodging in different places, I started to notice the three separate bins set out for us: a red-topped trash bin, a yellow-topped recycle bin, and a green-topped compost bin. Now, we compost at our own house, but it is voluntary and requires an extra expense and collection by a private contractor. Only one other house on our block has a compost bin. But in New Zealand it has become official and commonplace. In many places, every house had three bins collected by the municipality. Its municipalities clearly know that composting keeps tons (and tons and tons) of organic waste from ending up in landfills.

The biggest, most welcome surprise was thrust upon us the first time we shopped at a grocery store. No bags were offered at checkout. Paper and cloth bags were available to purchase for anyone who forgot to bring their reusable bags. But no plastic bags. Anywhere. The containers for leftovers at restaurants (which they call takeaway) were made of paperboard. Utensils were made of wood or bamboo. I was shocked and thrilled! New Zealand put a national ban on the sale or manufacture of single-use plastics in 2022. The ban includes plastic grocery bags, takeaway containers, and drink stirrers. We never saw a plastic straw. Replaced by perfectly good paper straws. Imagine the positive effect a ban in the US would have on our environment!

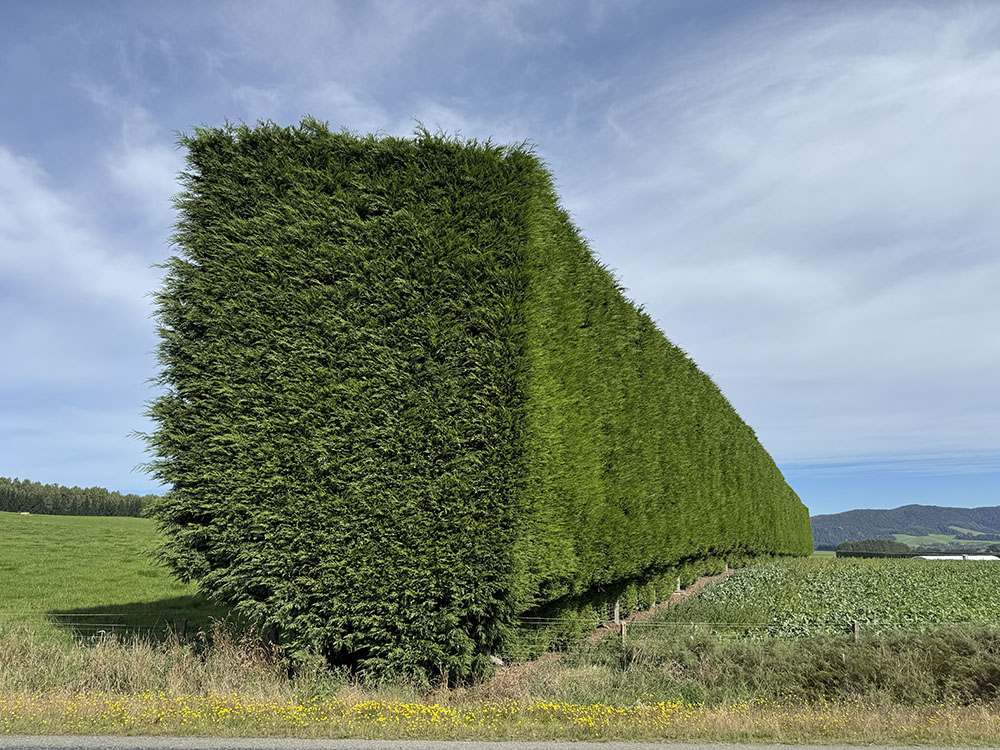

Prior to our road trip, I expected New Zealand to be entirely mountainous. I blame The Lord of the Rings (which was filmed there and featured scenes of mountains upon mountains). But driving around the country I was struck by how much open land there was. Mostly farms and pastureland. We saw plenty of cattle, several deer pens, and at least one with what looked like elk. But most of the pastureland was for sheep. By far. We even saw sheep grazing in a public park in Auckland, New Zealand’s largest city. In fact, there are four times as many sheep as people in the country.

Reflecting further, I realized that my feeling of open space wasn’t simply due to unpopulated land, though that was impressive enough! It was the lack of urban sprawl. There were cities, towns, and villages of various sizes, but they all pretty much ended abruptly with surrounding agriculture or open land. The majority of the beaches we saw were public and free of development. I’m sure it helps that the land is large compared to the population. At five and a quarter million people, New Zealand is less populated than Wisconsin, in an area almost the size of California.

Speaking of agriculture, one of the primary crops is … trees. The forest products industry is huge. We grow trees commercially in the U.S., of course. But it’s rarely as apparent here as it was along the highways and byways in New Zealand. Maybe we make greater efforts to hide the evidence by leaving a screen of uncut trees along the road. Maybe it’s because of the places they raise and harvest trees, which included steep slopes rising dramatically alongside roads. Regular rows of newly planted trees could be seen next to equally regular rows of tall trees ready for harvest, themselves next to completely denuded slopes that recently had been clear-cut.

Two parks that we visited especially exemplified contemporary New Zealanders’ environmental concerns. The 1,453-acre Tāwharanui Regional Park, north of Auckland, is located on a peninsula. This geographic feature allows the landward side to be completely fenced against invasive species of predators, such as weasels, opossums, and ferrets, which are devastating to native species. (New Zealand has no native mammals, so native populations, especially ground-nesting birds, easily fall prey to them.) We had to drive our car through a monitored gate to get into the park. It’s working. We probably heard more bird song during a one-hour hike than in most of the rest of our three weeks combined.

A forested section within Tāwharanui is even more protected. Our progress on the trail was interrupted at one point by a simple footwear-washing station. Its unavoidable gateway not only had shoe brushes (which sometimes you can see at the side of trailheads in the U.S.), but also a treadle that you step on to activate a soapy sole-rinsing spray. Signage explained that its purpose is to prevent visitors’ shoes from importing Myrtle Rust and other exotic seeds/spores/pollen etc. that are threatening kauri trees—New Zealand’s largest native tree species. We did see a number of young kauri trees, though no giants.

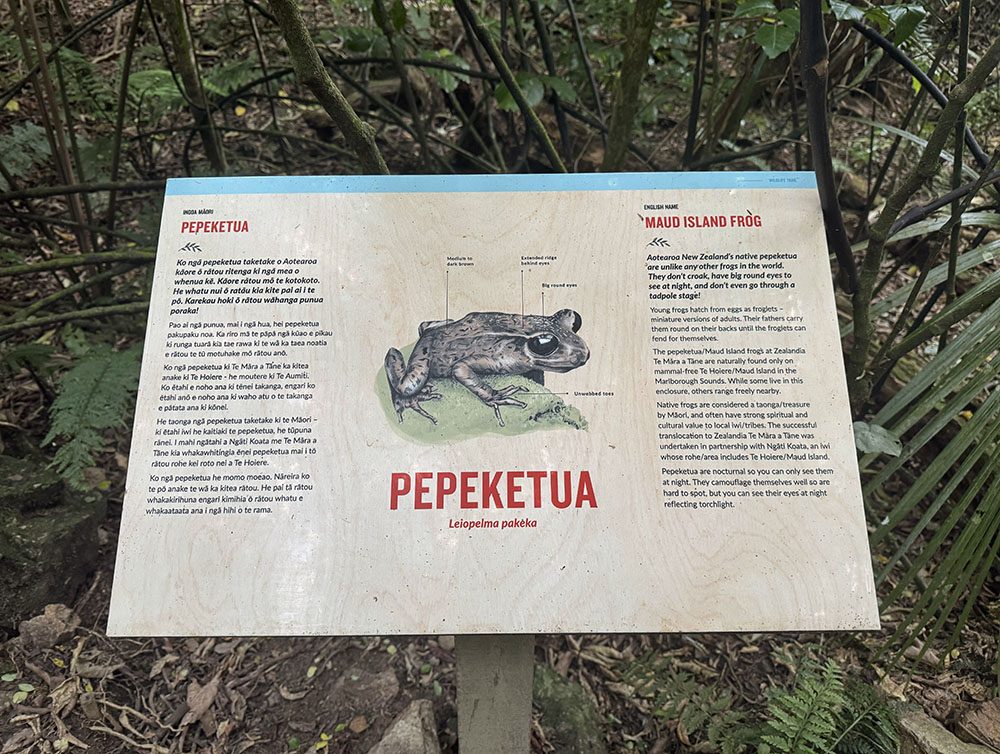

Zealandia/Te Māra a Tāne goes even further. Boldly billed on its website as “the world’s first fully-fenced urban ecosanctuary with an extraordinary 500-year vision to restore the valley’s forest and freshwater ecosystems as closely as possible to pre-human state.” (Note the phrasing; not just “pre-colonial” but “pre-human.”) Perhaps the most extraordinary thing about this park is its location within New Zealand’s capital city, Wellington. It takes almost five and a half miles of perimeter fencing to maintain the park’s ecosystem’s integrity. Zealandia/Te Māra a Tāne was established a mere 26 years ago; yet already it feels like a jungle. We saw plenty of birds here too, as well as a native reptile known as a tuatara within its own protected habitat. The tuatara looks like a lizard but is a genetically distinct order.

We also experienced the importance of indigenous Māori (tangata whenua) culture to the overall cultural composition of New Zealand (Aotearoa). Like the Indigenous peoples of North America, the Māori possess a special reverence for the land. In the history of colonization, New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to give its Indigenous people a voice in government, based on a treaty from the mid-19th century. And since 1987, Māori joined English as official languages of New Zealand. Everywhere we went we saw bilingual signage. I’m trying to imagine how different things in the U.S. might be if all of our signs were bilingual to show respect for Indigenous people, their history and co-presence on the land, no matter what their local languages might be in a given locale.

I loved the mountains, of course. And the beaches. And the beeches, as well as all the other strange yet beautiful plant and wildlife we encountered. As you can tell from this small selection of photos, there was a lot of nature to see, and to experience. The U.S. doesn’t take a backseat to anywhere when it comes to scenery, as far as I am concerned. No, the real takeaway from New Zealand is the possibility of how a society as a whole can move toward embracing nature and encouraging greater sustainability— as a matter of policy, social behavior, and psychology. After all, how we think about nature determines how we relate to it. I think I’ll go for a walk in the park….

Kia Ora!

(A Māori phrase meaning roughly “live well,” used in greetings and farewells.)

Note: The selection of photos that accompanies this story is a fraction of the whole. To see more from New Zealand, go to my Flickr album.

Eddee Daniel is a board member of Preserve Our Parks.

11 thoughts on "Foreign Correspondence: The Natural Realm in New Zealand"

Comments are closed.

Thanks for these pics. Eddee, I feel as though I went along on your trip to New Zealand!

Well done fellow traveler!

Since my wife and I have plans to travel there next year, I found your report, particularly fascinating and as always, I love your photos

Thank you for the eloquence of this reflection and the beauty of these photos! I so appreciate your generosity and thoughtfulness with which you share then!

THANK YOU! This was an awesome peek at your journey.

“…the real takeaway from New Zealand is the possibility of how a society as a whole can move toward embracing nature and encouraging greater sustainability— as a matter of policy, social behavior, and psychology. After all, how we think about nature determines how we relate to it. I think I’ll go for a walk in the park….”

Thanks Eddee. Reading this and looking at your photos was a perfect way to start a Saturday morning. Thanks for sharing not only the photos but the information about the culture as well as the nature.

Greetings Eddee! Thanks for sharing your trip. It looks like it was amazing in so many ways. It inspires hope for humanity’s future.

Thank you Eddee! Appreciate the insights and photos!

Beautiful. I was in NZ in about 1978. My most vivid memory was when we hit a sheep in our tiny rental car. Unfortunately, killed both the sheep and the car. It made for an interesting afternoon.

Loved the New Zealand photos. The tree hedges brought many memories.

Terrific photos, Eddee!