Cahill Square Park: Finding What’s Hidden in Plain Sight

August 9, 2025 | Topics: Places

By Emily Grandy

The cicadas’ pulsating whir drones overhead, making the first day in August seem hotter than it really is. Aside from the cicadas, the only sounds in this suburban neighborhood are the children shrieking with delight and the thwack of a tennis ball batted back and forth: puck…puck…puck.

I’ve come to Cahill Square Park in Whitefish Bay, a multi-use recreational space with a baseball field, tennis courts, a playground, a butterfly garden, and a large stormwater detention basin. It feels more utilitarian than most of the parks I read about in The Natural Realm blog, but I’m here to challenge myself. I want to see whether I can discover a wealth of nature here, in this manicured, square park.

Usually, I prefer to visit parks that boast more natural landscapes, with meandering trails that cater to hikers and birdwatchers, and rivers that attract kayakers and fishermen. But as a writer, novelist, and ecological activist who lives in an urban environment, I want to seek nature a little closer to home. Say, in a backyard park.

My reasons for choosing Cahill Park are twofold: it is not the most obvious place to look for wildlife. Sure, there are a few mature basswoods and a bunch of Norway maples dotted throughout the park, but at first glance it appears to be mostly lawn, a shallow-rooted, non-native cultivar that supports almost no wildlife, and retains almost no water when it rains. I’m standing at the top of the drainage basin, a massive square indentation that occupies about a quarter of total park land here and dips down about six feet from ground level along a gradual slope. It, too, is lined with lawn, but there’s a curious upgrowth of green along one side.

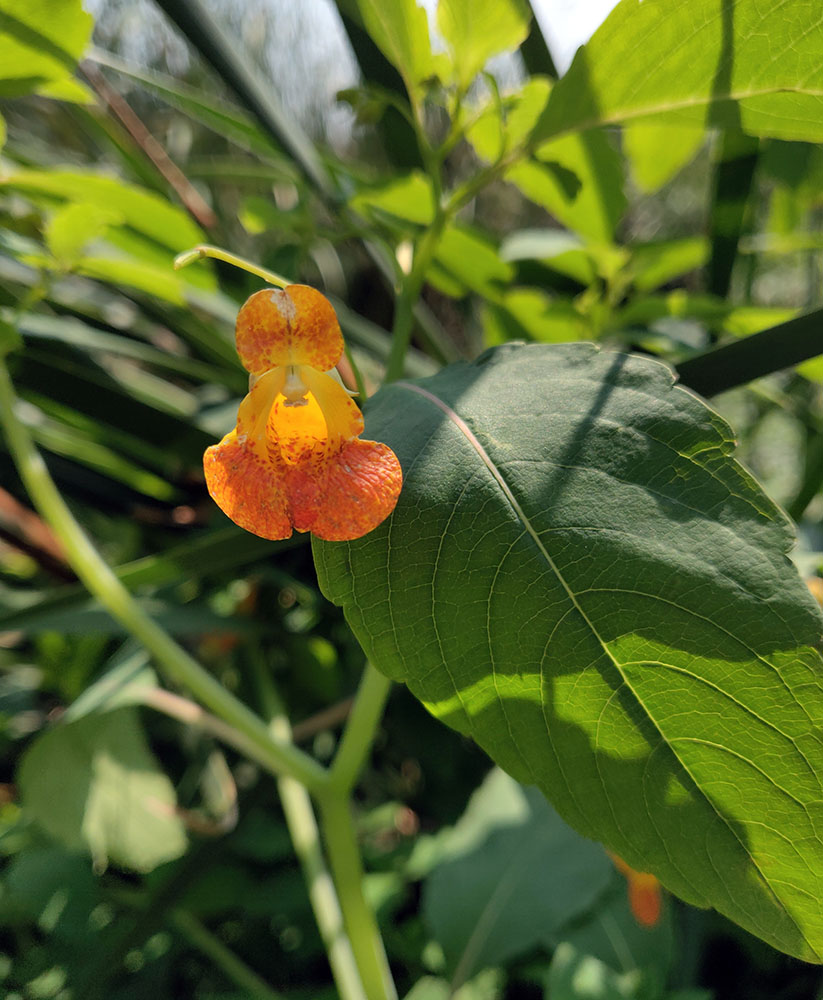

This little cattail marsh is long and narrow and packed with dense green fronds that reach well above my head. The texture of the leaves is dense and slippery, and when I snap one in half, the inside is full of tiny air pockets. Surrounding the perimeter of the marsh are clumps of jewelweed with their dainty orange blossoms that droop as bumblebees enter, seeking nectar. They wiggle and push against the petals to back themselves out again. There’s goldenrod here too, just beginning to open. Soon, it’s froth of yellow flowers will open, another pollinator favorite. Then I hear another sound: konk-a-ree!! The unmistakable call of a Redwing Blackbird overpowers even the unwavering cicada thrum.

This is the second reason I’m here, to visit this little wetland. I’m told it’s only 0.18 acres (less than 8,000 square feet), a fraction of the 9-acre park, but it’s home to a surprising diversity of wildlife. The cattail marsh grew up accidentally within Cahill Park’s massive drainage basin, which was designed to hold runoff during flooding events. Since then, it has become a refuge for nesting Redwings and rare wetland-dependent species like Sora and Virginia Rail. Other water-loving creatures live here too: mallards, frogs, toads, dragonflies, damselflies, and plenty more I cannot see with the naked eye. My friend and local biologist, Charlotte Catalano, has documented over 90 species here.

Unfortunately, this little marsh is under threat. Wildlife enthusiasts are rallying to protect it. According to the official report from the contractor, the reasons for wetland removal are that “The Village of Whitefish Bay hopes to eliminate the standing water and nuisance vegetation within the swale to promote a more functional and aesthetically appealing public space.”

While open green space can support recreational activities, the wetland occupies only 2% of total land area in a highly manicured park designed to accommodate a number of activities, including baseball, tennis, and a brand-new playground for children. The wetland represents another activity: an opportunity for visitors to engage with nature. As anyone familiar with The Natural Realm blog knows, wildlife viewing is a relaxing and sensorily engaging pastime for people of all ages and ability levels. Nationwide, wildlife viewing, nature photography, and birdwatching in particular, have become increasingly popular pastimes.

Wetlands provide other benefits, too. They mitigate flooding by capturing and storing water, prevent erosion by slowing the passage of water, and decontaminate water by removing pollutants and sediments, keeping our lakes, streams, and drinking water clean. Towns like Whitefish Bay have a unique opportunity to help protect our Great Lakes by allowing emergent marsh plants to do what they do best: filter out pollutants and runoff before they can contaminate Lake Michigan.

I circle the marsh, keeping my distance to avoid disturbing the Redwings feeding their recently fledged young, who rise and bob on the cattails. A willow tree, another water-loving species, has grown up here too, at the far end of the marsh. It’s narrow, silvery leaves twist and sway in the breeze. Hidden amongst its branches, goldfinches tweet back and forth.

I circle the willow and am delighted to discover a small prairie garden growing tall and bright in the afternoon sun. Here, I find another host of native plant and invertebrate species. Bee balm, with its frilly, lavender-colored flowers. Spikey white balls of rattlesnake master. Stalks of vervain, cup plant, black-eyed Susan, common milkweed, blazing star, Joe-pye weed, nodding onion, and a dozen others. Bees and wasps and butterflies, all sorts of pollinators, float and land, visiting flower after flower, passing along pollen in their quest for nectar.

This is what cohabitation can look like. This pollinator garden was planted by locals in an underutilized corner where bare lawn used to be. Now it feeds insects and adds color, interest, and beauty to this recreational space.

But I’m saddened when I try to understand why one habitat, made by people, is deemed more valuable than one that wasn’t. The flowers can stay, but the cattails must go? Who gets to decide which habitats are of value and which are not? Maybe we should let the residents of those habitats have a say.

It’s easy to see the beauty in flowers, and most of us want to protect what we perceive as beautiful. Perhaps finding beauty requires us to take a closer look at the creatures and places that were historically undervalued. Wetlands—a term encompassing many types of habitats, including marshes and swamps—were turned over for agricultural land all across this country, but especially in the Great Lakes region. Yet, according to The Wisconsin Wetlands Association, 75% of all Wisconsin wildlife depends on wetlands at some point during their life cycle.

More than half of Wisconsin’s historical wetlands have been lost to agriculture and development. It’s difficult to appreciate something you are never exposed to, and don’t understand. If you live in a suburb without a single remnant wetland, you may think water is meant to flood streets and basements, or drain into a retention basin, rather than be held and moved by an elaborate ecosystem. You may never have heard frogs chirping or seen turtles sunning themselves on warm logs. You may be entirely unfamiliar with waterlilies, irises, and dragonflies. Waterfowl, and the predators that hunt them, need these places too. But without opportunities to observe these beings where they live, how can we foster an appreciation for them?

It’s far easier to destroy a habitat than restore it. Before we lift the shovel, let’s kneel down in the soil, part the reeds, and see who’s living there.

Parks with natural landscapes and trees that hide development from view not only provide necessary habitat and waystations for wildlife, they offer psychological benefits for people, encouraging us, perhaps, to decentralize our own perspectives and desires for a time. But maybe parks like Cahill are just as essential, for they offer an even greater number of local residents an opportunity to connect with the natural world in small but meaningful ways. Through fireflies at dusk and monarch caterpillars nibbling on milkweed. Maintaining small examples of habitat across the street from where people actually live, instead of a long drive away, is an important conduit through which we can connect with wildlife on a hyper-local level. Those of us who already love and appreciate natural landscapes and restored ecosystems often look to bigger, wilder spaces for recreation and fulfillment. But for others, a more approachable entry point to cherishing wildlife might be better positioned closer to home.

Adding butterfly gardens, native swales, mini marshes, and plenty of benches, paths, and signage to urban parks can help kindle and foster a relationship between tentative novices and our more than human kin. I urge you to visit these places, advocate for them, and work to attract a bit more wildlife.

*If you would like to support our effort to protect the Cahill Square Park cattail marsh, please use this link to sign the petition to the Village Trustees.

Related stories:

Close Encounters in a Suburban Enclave or Why Neighborhood Parks Matter

Indian Creek Woods and Indian Creek: Rebounding with Life in Fox Point

Silver Spring Park: The Return of the Natives

All photographs by Emily Grandy, except as noted. The photo collage at the top is by Charlotte Catalano. Emily Grandy is a biomedical editor and an award-winning novelist of two books, Michikusa House and Cupido Cupido. She writes literary fiction and nonfiction with an ecological focus. You can find her work at emilygrandy.com.

Editor’s note: We welcome Emily Grandy is a guest contributor to The Natural Realm. Preserve Our Parks has not taken a position on the efforts described in the story.